WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following article contains images of deceased persons.

This article recounts the personal story of my ongoing desire to materialise decolonising practices in the course of my life as an academic-activist coming from a migrant background and living and working within the context of the Australian settler-colonial state. It is a story of impassioned commitments, transformative moments and solidary convergences. It is a story inscribed within the hegemonic power formations of settler colonialism, white-supremacist racism and northern Italian anti-southern racism – as key factors that have shaped my itinerary. It is, crucially, a story of enduring friendships with Indigenous Elders, activists and artists and our collaborative moves to instantiate decolonising practices (Langford-Ginibi, 1988; Pryor, 1998; Birch, 2000 and 2007; Watson, 2007; Black, 201; Tuhiwai Smith, 2012; Bell 2014).

Some decades ago, at the end of a class that I was teaching at the University of Newcastle, one of my students approached me and apologised for not having submitted one of her assessment tasks. She explained that she had spent the weekend assisting in the organisation of a rally protesting for Aboriginal land rights. I was, at that stage in my career, a postgraduate casual tutor. It was 1990 and Indigenous communities were continuing to assert, as they had since the moment of colonial invasion, their right to self-determination and to land rights. I said to the student that I was genuinely glad to see she had her priorities right and that her reason for the deferred submission automatically qualified her for an extension. Unbeknownst to me, this would turn out to be a pivotal moment in my life.

I would no doubt have forgotten this incident had it not returned to me in the most unexpected way a few years later. It was 1994 and I had commenced my first full-time position at the University of Wollongong. One afternoon I received a call in my office. The caller at the other end began: «You probably don’t remember me, but I was in one of your classes at Newcastle. I once asked you for an extension for one of my essays and you granted it to me after I said I’d not been able to submit the essay on time because I had attended an Aboriginal land rights rally. I never forgot that». I actually remembered both the incident and the student-caller: Barbara Nicholson. We began to engage in an enthusiastic conversation on Aboriginal land rights and then Barbara mentioned that she was a member of the Wadi Wadi people of the Illawarra (I did not presume to know at the time of granting the extension whether or not the student before me was Aboriginal). Barbara then began to unfold a profoundly disturbing story of structural racism and how it had impacted on her family. She said that one of their Elders, Aunty Joan Wakeman, had recently died but that the funeral home that they had approached had refused to bury her unless the family paid the full sum for the funeral up front, and not in instalments as they requested, as, the funeral home director pointed out to them, «Aboriginal people never pay their bills». Consequently, a hugely respected Aboriginal Elder was left in a state of undignified suspension in a local morgue as the family desperately tried to raise the funds to bury her – which they eventually managed to do. I was upset to hear of this distressing incident and said to Barbara that we needed to make the story public in order to expose the racism of the funeral home. It occurred to me as we were talking that I had just been given the resources to turn one of my units into a distance-education module that would entail the production of a number of videos based on the unit’s content and that would be screened as weekly episodes on the Special Broadcasting Service (sbs) television channel.

Barbara was excited at the prospect of collaborating on this project and we immediately decided to put the project into play. As we talked about the project, we realised that it would be best to situate the story of the funeral home’s racism within the larger narrative of settler-colonial violence that attended the occupation of Wadi Wadi land. Barbara and two Wadi Wadi Elders, Aunty Joan Carriage and Uncle Alan Carriage, became the leads in telling the story in our documentary (figure 1).

Figure 1. Aunty Jean Carriage, Barbara Nicholson and Uncle Alan Carriage. Still from Contemporary Colonialism and the Struggle for Aboriginal Self-Determination, 1996

Source: photo by Joseph Pugliese

Barbara’s daughter, Tess Allas, curator of Indigenous art, also came on board. Tess brought to the documentary an extraordinary cast of Indigenous artistic talent working in the Illawarra and on the aesthetics of resistance that they materialised through their creative works (figure 2). The two-part documentary was titled Contemporary Colonialism and the Struggle for Aboriginal Self-Determination. The documentary was a collaborative work in every sense of the word. It screened on sbs television in 1996.1 The friendships formed in the time of that collaboration have been enduring.

Figure 2. Tess Allas discussing Kevin Butler’s painting Assimilation 1995. Still from Contemporary Colonialism and the Struggle for Aboriginal Self-Determination, 1996

Source: photo by Joseph Pugliese

I tell this story as it underscores one of my life-long concerns: how do I, as a migrant subject, living and working on Awabakal, Wadi Wadi, Gadigal and Darug people’s lands, and as someone who has clearly benefited from the ongoing usurpation of Indigenous land and sovereignty, proceed to instantiate decolonising moves in practice? I emphasise in practice as I have viewed my position, since the beginning of my career in academia, as one that must translate academic knowledges into transformative activist practices that are oriented by social justice outcomes. And I place the term «migrant» in scare quotes in order to draw attention to the manner in which it necessarily encompasses both Anglo and Celtic Australian subjects who continue to nativise their usurpation of Indigeneity by using the term «migrant» to refer exclusively to all non-Anglo-Celtic subjects – thereby working to consolidate their illegitimate host/guest power nexus.

The social justice orientation that has underpinned my pedagogy and research has deep roots in my own lived history as a Calabrese migrant growing up in 1960s-70s assimilationist Australia and from my first-hand experience (and study) of the northern Italian anti-southern racism that has so constitutively shaped South/North relations since the time of ostensible Italian «unification» (see Ricatti, 2018 and his list of relevant references). The fraught racialised location that I embodied – that effectively positioned me on the one hand as an unAustralian «dago» and «wog» in an Anglo-Australian context and, on the other hand, as a «terrone» who, in the white-supremacist view of northern Italians, was racially coextensive with either Africans or Arabs – obliged me to adopt an affirmative sense of double non-belonging: neither Australian nor Italian, rather, a diasporic outlier compelled to negotiate the locus of the non.

I mark this fraught embodied status as it fuelled my understanding of how racism impacts in both violently physical and symbolic modalities on its targeted subjects. I have also written on how migrant subjects, such as southern Europeans who were once racially reviled by Anglo-Australians, have often assiduously aspired to become what I term «super-assimilated» settler subjects; as such, they reproduce white-settler positionalities and values – often in stridently performative modes in order to appear whiter than white and more Anglo than Anglos (Senator Cori Bernardi, in the context of white-settler politics, is a case in point). Moreover, following the abolition of the White Australia Policy and the consequent migration of Blacks and people of colour to Australia, migrants who had previously been inscribed by a not-quite-white status (such as southern Europeans) have capitalised on their recalibration by the Australian state up the racial hierarchy towards whiteness. Super-assimilated migrants have laboured to secure their assumption of a white racial status precisely by reproducing the very racist values and practices of the dominant settler culture and, simultaneously, by erasing their own complicity in the maintenance and reproduction of the Australian settler state.

Having said this, however, I want to pause for a moment in order to complexify my argument. Even as some not-quite-white migrant ethnicities have been conferred, following the racial recalibration that I mentioned above, a white racial status (and all of the privileges that accrue from this), not all migrants previously classified as not-quite-white have been enabled to make this transition – as though it were simply the case of designated subjects seamlessly embodying the racial categories or ethnic descriptors that a state decides to impose upon them, regardless of the embodied phenotypical differences that insist on racially marking them otherwise. Race, qua whiteness, is never a unitary nor homogeneous category. As a historically contingent and socially constructed category, it is always shot through with embodied contradictions. Specifically, some southern European migrants have continued to experience the lived racist effects of appearing to be racially other precisely because their phenotypical attributes mark them, for example, with the loaded descriptor «of Middle Eastern appearance» and the racist effects that ensue from embodying this charged configuration (Pugliese, 2003).

With the apparent validation of migrant cultures and heritage by the Australian state following the legislation of a number of «multicultural» policies, non-Anglo migrants began to reclaim key migrant sites, such as the Bonegilla Migrant Reception and Training Centre, and to revalorise them as heritage places. Concerned by the manner in which many migrant communities were writing their histories of migration and settlement in Australia without acknowledging the Indigenous peoples upon whose land they established their very livelihoods, I published an essay, «For a Decolonising Migrant Historiography» (Pugliese, 2002) exhorting non-Anglo migrants to acknowledge their own complicity in contemporary settler practices and to work with Indigenous peoples towards dismantling the colonial hegemony of the Australian settler state.

My desire to continue to develop and materialise a social justice politics committed to anti-racist and decolonising practices led me to join the Indigenous Social Justice Association (isja) in early 2000. Co-founded (with Ray Clark) by the late and great Uncle Ray Jackson, isja’s mandate was to instantiate decolonising and anti-racist practices across a broad range of institutions and to work to achieve justice for the victims, and the families of victims, of institutional violence, racism and injustice (figure 3).

Uncle Ray was an extraordinary mentor.2 He insistently brought into focus in his social justice work the manner in which the prison-industrial complex was instrumental in consolidating the settler state’s desired elimination of Indigenous people through practices of incarceration and their serial deaths in custodial settings. All of his work was informed by this non-negotiable fact: that Indigenous people had never ceded their sovereignty or their lands and that neither the Australian government nor its laws had the authority to speak on behalf of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. He evidenced this non-negotiable fact through such memorable events as the Aboriginal Passport Ceremonies.

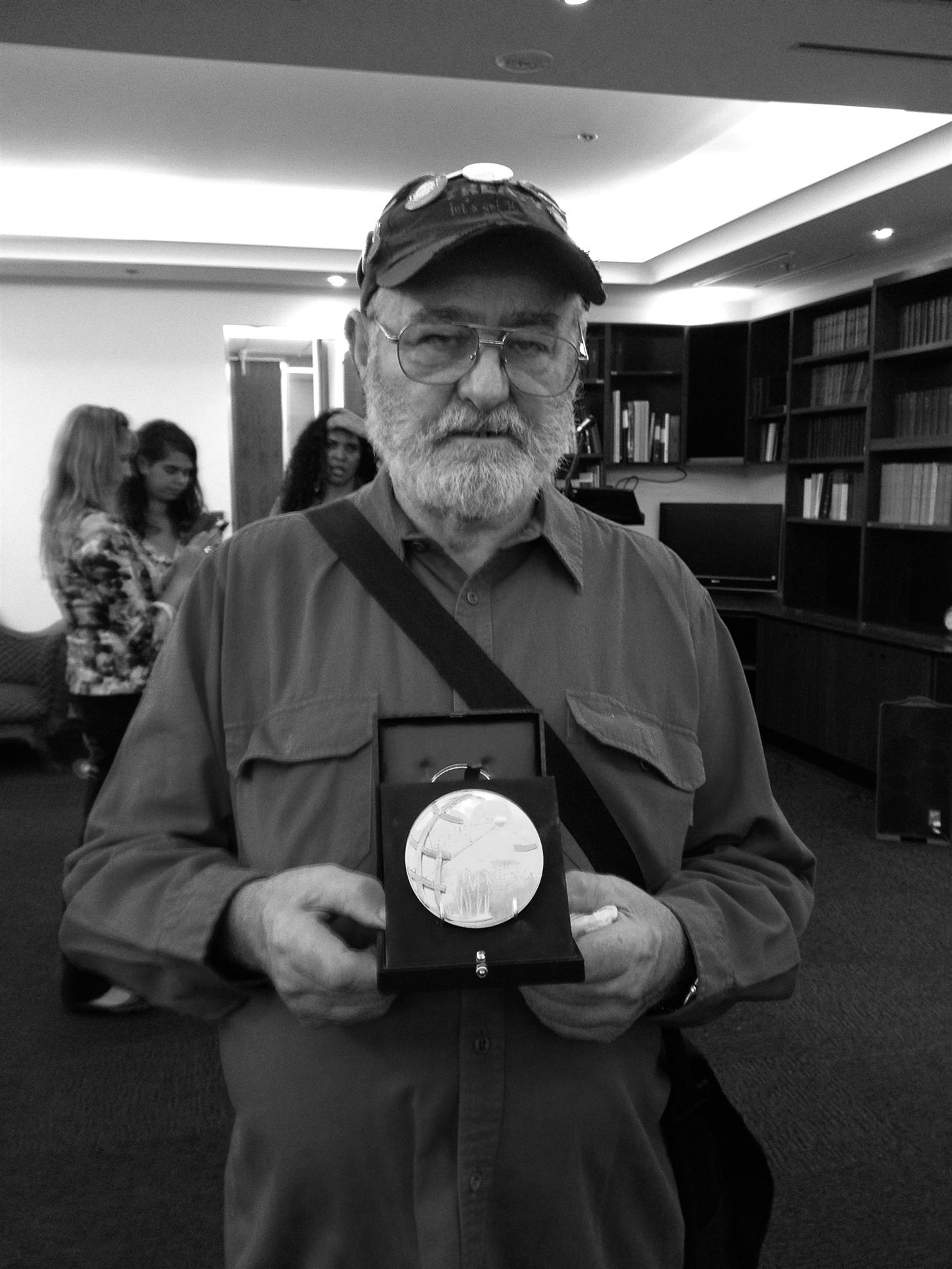

Figure 3. Uncle Ray Jackson holding his French Human Rights medal, French Consulate, Sydney, 2015

Source: photo by Joseph Pugliese

The first Aboriginal Passport Ceremony was organised by Uncle Ray, together with a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous isja activists, in September 2012; it was staged at The Settlement, Redfern. Uncle Ray described the aims of the ceremony thus:

The issuing of the Passports covers two areas of interactions between the Traditional Owners of the Lands and migrants, asylum seekers and other non-Aboriginal citizens in this country. Whilst they acknowledge our rights to all the Aboriginal Nations of Australia we reciprocate by welcoming them into our Nations (cited in Pugliese 2015).

I have vivid memories of the excitement felt by the isja collective in seeing the first Aboriginal Passport Ceremony come to fruition. That embodied sense of non-belonging that I discussed above was dispelled by Uncle Ray Jackson’s moving conferral to me of an Aboriginal passport during the course of the ceremony (figure 4).

Figure 4. Uncle Ray Jackson conferring an Aboriginal Passport to the author, The Settlement, Redfern, 2012

Source: photo by Joseph Pugliese

In insisting on Aboriginal peoples’ unceded sovereignty and their right to determine to whom they would offer hospitality, Uncle Ray overturned the settler state’s illegitimate host/guest nexus, and its violent border politics, by also extending his welcome to the asylum seekers and refugees detained in Australia’s onshore and offshore immigration prisons. In the context of the Aboriginal Passport Ceremonies, he not only issued passports to a number of asylum seekers and refugees, but he also proceeded to acknowledge, in an unforgettable gesture, the absent asylum seekers and refugees who could not attend the ceremony because they were locked up in Australia’s immigration prisons or because they had died within those same prisons. In order to mark their enforced absence from the ceremony, he placed centre stage an empty chair over which was draped the Aboriginal flag (figure 5).

Figure 5. The Aboriginal flag draped over an empty chair, Aboriginal Passport Ceremony, The Settlement, Redfern, 2012

Source: photo by Joseph Pugliese

As a material continuation of Uncle Ray’s legacy, Suvendrini Perera and I, working with an international team of collaborators in the us, Canada and the uk, developed the Deathscapes: Mapping Race and Violence in Settler States project. The aims of the project are to bring into focus the transnational structures of incarceration and elimination that so often result in lethal outcomes for Indigenous people living under settler rule; and, concomitantly, to underscore how the usurpation of Indigenous sovereignty by settler states is predicated on violent moves to secure its borders and thus to consolidate its illegitimate sovereignty (simply put, no control over one’s borders, no legitimate claim to being a state). Deathscapes critically examines the nexus, with all of its inbuilt and crucial differentials, of Indigenous and refugee imprisonment and death in the context of three settler states – with the uk hub bringing into focus the originary point of empire and colonial power.

Figure 6. Dr Ray Jackson’s academic gown with the Aboriginal flag. His Honorary Doctorate was awarded posthumously by Macquarie University, 2016, as Uncle Ray died just prior to the award ceremony

Source: photo by Joseph Pugliese

I titled this article «For the Instantiation of Migrant Decolonising Practices» as the preposition for critically emphasises both the commitment to practices of decolonisation and the fact that these practices have a futural orientation. The practices that I outlined above defy the seeming impossibility of dismantling the settler-state hegemon because they work to materialise points of convergence between Indigenous and non-Indigenous subjects committed to the realisation of decolonisation. Such practices emerge as synchronic decolonising instantiations within the diachronic continuum of unceded Indigenous sovereignty that is scored by the timeless refrain: «Always was, always will be Aboriginal land». As material practices, they fissure the seeming impermeability of the settler hegemon; and, as ruptural acts, they open up a horizonal space in which non-Indigenous subjects within this country collectively acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the Lands and the enduring Indigenous Nations that continue to challenge the illegitimate authority of the settler state. The Aboriginal Passport Ceremonies, understood in this context, proleptically delineate a destinal trajectory that encompasses both the pre-colonial and the genuinely post-colonial. In the schema of this trajectory, the violent interregnum of the Australian settler state will be seen, after its demise, as an interchronic phase marked by its own auto-immune expiry date.

Acknowledgements

Photos of Aunty Joan Carriage, Uncle Alan Carriage, Barbara Nicholson and Tess Allas reproduced with kind permission of Tess Allas. Photos of Uncle Ray Jackson reproduced with kind permission of Carolyne Jackson.

Notes

1 Contemporary Colonialism and the Struggle for Aboriginal Self-Determination was subsequently nominated for an Australian Society for Educational Technology Award (1996), receiving a Commendation, and it was also nominated for the United Nations Association of Australia Media Peace Award (1996).

2 As way of paying homage to Uncle Ray’s outstanding social justice achievements, in 2015 I successfully nominated him for the prestigious French Human Rights Prize, and he and isja were awarded €20,000 to continue their social justice work. In 2016 I nominated Uncle Ray for an Honorary Doctorate, which was awarded posthumously to him by Macquarie University.

Bibliography

Bell, R., «Public Lecture 8: Richard Bell», University of Technology, Sydney, 28 April 2014.

Birch, T., «The Last Refuge of the “Un-Australian” Subaltern, Multicultural and Indigenous Histories», UTS Review, 7.1, 2000, pp. 17-22.

–, «“The Invisible Fire”: Indigenous Sovereignty, History and Responsibility», in Moreton-Robinson, A. (ed.), Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters, Crows Nest, Allen & Unwin, 2007.

Black, C. F., The Land Is the Source of the Law: A Dialogic Encounter with Indigenous Jurisprudence, London and New York, Routledge, 2011.

Deathscapes: Mapping Race and Violence in Settler States, in https://www.deathscapes.org/.

Langford-Ginibi, R., Don’t Take Your Love to Town, Ringwood, Penguin, 1988.

Pryor, B., Maybe Tomorrow, Ringwood, Penguin, 1998.

Pugliese, J., produced in collaboration with the Wadi Wadi people, Contemporary Colonialism and the Struggle for Aboriginal Self-Determination, video documentary, University of Wollongong, 1996.

–, «Migrant Heritage in an Indigenous Context: For a Decolonising Migrant Historiography», Journal of Intercultural Studies, 23.1, 2002, pp. 5-18.

–, «The Locus of the Non: The Racial Fault Line “of Middle Eastern Appearance”», Borderlands, 2.3, 2003, in http://www.borderlandsejournal.adelaide.edu.au/vol2no3_2003/pugliese.htm.

–, «Geopolitics of Aboriginal Sovereignty: Colonial Law as a “Species of Excess of Its Own Authority”, Aboriginal Passport Ceremonies and Asylum Seekers», Law Text Culture 19, 2015, pp. 84-115.

Ricatti, F., Italians in Australia: History, Memory, Identity, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Tuhiwai Smith, L., Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, London, New York and Otago, Zed Books and Otago University Press, 2012.

Watson, I., «Aboriginal Sovereignties: Past, Present and Future (Im)Possibilities», in Perera, S. (ed.), Our Patch: Enacting Australian Sovereignty Post-2001, Perth, Network, 2007.