Cume ti vidanu te descrivanu!

[As they see you, they describe you!]

(Calabrese proverb)

Seeing the sovereign Aboriginal warrior woman shifts the gaze, directs attention and brings into focus a different being. There is strong potential for her to be found in each Aboriginal woman

(Bunda, 2018, p. 5).

Blak women writers, poets, artists, scholars and community workers disrupt dominant colonial and patriarchal narratives in both community and public space in Australia1. Their work speaks back against dominant white voices and those associated with whiteness. The history of Italian settlers in Australia need to acknowledge and value blak perspectives. As a child of both an Aboriginal woman and a Calabrese migrant father, I have resisted the categorisation of Italians as white. I’m sure that when my father was called a wog2 he wasn’t associated with whiteness, but the racism he encountered was. And perhaps I resist whiteness because this means acknowledging a part of myself that I don’t embrace, because it represents cruelty and oppression.

I am a First Nations woman who is Wemba-Wemba and Gunditjmara. I was raised by my mother, grandmother and Aunties, Aboriginal women in country Victoria, «on Country» and predominantly away from my father’s Calabrese, working class and migrant family, who was living in the Western Suburbs of Melbourne. My sense of identity and knowing has been informed by what Moreton-Robinson (2000, p. 16) calls relationality, that is, «Knowing the self through others, and others through the self». It also means that I simultaneously experienced «double» racism for my Indigenous identity and my Italian «otherness», including bullying and sexual violence.

Aboriginal women have been and continue to be the most marginalised people in Australia, and have been subjected to various forms of violence, both historical and ongoing. Though always at the forefront of political, psychosocial and cultural resistance and survival, our knowledge and practices are often omitted and rendered invisible in academic and public forums. My artistic practice, writing, academic work and community activism are all informed by my deep sense of Indigenous identity, but also by my experience of being viewed as being some kind of «outsider» by non-Aboriginal people and white people; and understood by my Koorie family as also having Italian blood, but being no less Aboriginal to them.

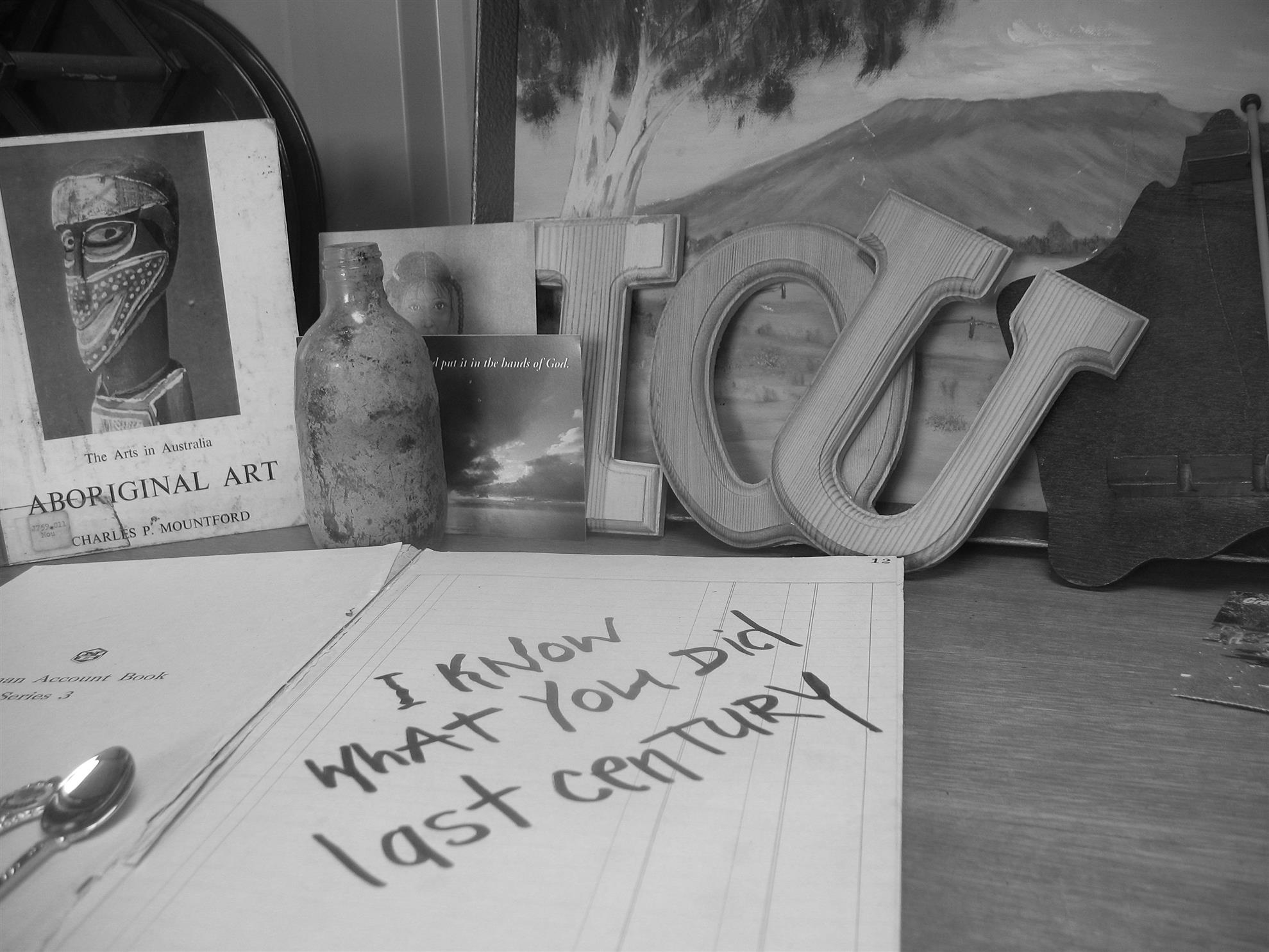

Figure 1. I know what you did last century

Source: Paola Balla, 2010

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have non-Aboriginal blood, including that of Italian migrant grandparents and parents. Yet the interest in their stories from Italian-Australian academics has not been evident until the work of the public Forum at the Diaspore Italiane Conference in Melbourne in 2018.

My invitation to this Forum was surprising, but welcome to me. Participating in the Forum was a slightly disassociating experience. Apart from socialising with my Calabrese family, I had never attended a large gathering of Italian people. For example, I had never visited the Museo Italiano in which the public Forum took place. Some of this brought a feeling of shame, not cultural shame as known in an Aboriginal way; rather the embarrassment that often visits me in relation to not knowing Italian language, religious or cultural customs, and feeling not «Italian enough» for my family, or the broader Italian community. Whereas in a white and settler Australian context, I have had to disrupt pre-conceived notions of what an «authentic» Aboriginal is and not really being «Aboriginal enough» (Smith, 1999).

Participating in the Forum, and feeling grateful for the invitation, I also appreciated the Forum’s positioning of me to speak first and to situate an Indigenous presence and perspective. It is also a disruptive and challenging position for me to be placed in. As far as I knew I was the only Aboriginal person in the room, and I felt somewhat objectified and could feel the scrutiny from some members of the audience.

I was required to respond to what Joseph Pugliese that evening described as a «flattening» question, which was posed to me at the end of the panel. The question focused on an old argument, and one that I had already faced from my own Calabrese father. The question, which I also experienced as an accusation, focused on capital; it was prefaced with, «I know that there have been bad things that happened to Aborigines, but… (at this point I knew exactly what was coming)… why don’t Aborigines just work hard and move forward like us Italian migrants have?».

In answering, I shared the fact that my father had already posed that question to me when I was only eleven years old, while visiting him on my yearly school holiday. At the time I was living three hours away, on Country, with my mother and grandmother, who were poor, discriminated against (historically and currently), and who had both suffered rape at the hands of non-Aboriginal men. In my mother’s case, she had been the victim and survivor of my father’s violence. In fact, this was the reason she left him. This included him not supporting me or Mum financially.

From this position I had to disrupt the flattening and reductive question that lurks historically within many migrant communities towards Indigenous people in Australia. The one in which migration requires participation in a particular, assimilationist racism towards Aboriginal people.

While the principle aim of the public Forum was to reframe dominant historiographies, memory and public discourse about the Italian diaspora from a decolonising perspective, I found myself disrupting the Forum as a blak woman’s voice, as both Indigenous and migrant, both sovereign and settler. I have had to grapple intellectually and emotionally with the complicit nature of my father and his family’s wealth building, whilst watching my own family struggle financially and die of preventable chronic illnesses, and trauma impact our collective wellbeing.

I believe I played both a contestatory and cohesive role within the Forum, in which I presented a lived experience first person account of sovereignty impacted by Italian settlers, as a member of a settler family, but not as a member of a settler community. If the aims of the Forum are genuine and followed through, I anticipate the new dialogues and outcomes of this Forum have the potential to utilise Italian settler privilege to advance the decolonial project in Australia.

My nonna was born in Motticella, Reggio Calabria in 1913. My father was born in 1948 and came to Australia with his parents as a thirteen-year-old in 1961, he didn’t speak English and still speaks Australian English with a heavy Calabrese accent. My father’s accent used to embarrass me as a child, which pains me now, and I was afraid that if he showed up (as he continually promised but never did) I would have had to deal with his presence amongst the ignorance and racism of a town I was already struggling with.

My Aboriginality already brought me much racism and attacks on my body. Being a «wog» was another burden I wasn’t ready to carry at primary school. My staunch Wemba-Wemba and Gunditjmara single mother was raising my brother and me on Yorta Yorta Country, in a small country town on the Murray River. My parents got together on Boon Wurrung Country in St Kilda.

Despite school being a place of violent racial bullying for me, I loved learning and felt I had a future through education. My grandmother Rosie, an artist and poet, told me from the age of nine, to «get educated, go as far as you can, and beat them at their own game». I didn’t start to comprehend the significance of this until my PhD commencement. Now a PhD candidate, I know my grandmother’s spirit has guided this process, particularly in the most challenging of times. The struggle that Aboriginal women experience in Australia has also been my story.

Perhaps my nonna Paola is also smiling at my achievements, I know that she worried for me and was not able to be in my daily life in the way that my Nanny Rosie was. But, nonna’s insistence and proficiency with a microphone at weddings and family celebrations inspired me to speak up. My nonna also wrote poetry, and the story of her life and how she came to meet my grandfather.

My Nanny Rosie was so beaten down by life and racism that sometimes showing up to events was too much for her. I would watch her closely as she would ready her hair, make up, jewellery, outfit and bag to leave for somewhere my mother wanted to take her.

Many times I watched her nervously click her forefinger and thumb together in a rhythm that would end with her knee shaking, and then her head at my mother with resignation that she would not actually be leaving the house. It was heart breaking. In 2012, I remembered my grandmother when I had a mental health breakdown and I was unable to leave the house. I was reminded of the paralysis that kept her home, away from the world that actually needed to hear from her, needed to hear her great laugh, her stories of colonial horror and survival.

Tracey Bunda (2018, p. 5) writes of the «sovereign care» practiced by Aboriginal women and their «primary roles in holding our families and communities together». Because of this care from my Wemba-Wemba matriarchs I was able to relate to my Calabrese identity and family history. They encouraged me to visit my Calabrese grandparents; my grandmother had great compassion for them missing me but worried about me being away too.

Aboriginal women’s autobiographical work (Ginibi Langford, 1988; Tucker 1977) situates the herstory as significant to the understanding of Aboriginal women’s care, love, resistance, identity and community. The story telling of my Nan and mother in my childhood echo this. Moreton Robinson (2000, p. 1) states that «the landscape is disrupted by the emergence of the life writings of Indigenous women whose subjectivities and experiences of colonial processes are evident in their texts».

Writing and art have afforded me an opportunity of disrupting the cultural landscape that does not see me and can only «read» me if I write myself into it. I do this through my curatorial, visual and community arts practice. Writing has been a process in which I enact my sovereignty to understand the place I was born into: the only child of my parents, but only one of many Aboriginal and Italian children born to Aboriginal and Italian parents.

I also write it for my children and my children’s children. I refuse dna tests and problematic commercial companies that mine people’s ancestry. I refuse it because my identity is a lived experience, not a disembodied abstract scientific exercise. It is lived theory; a story of connection, reciprocity, responsibility and respect (Smith, 1999), and «relationality» (Moreton-Robinson 2000, p. 16).

So, how do I know my Calabrese-ness? I know it through knowing my Aboriginality. My Aboriginal matriarchs taught me to respect this within myself, despite being physically separated from my Italian family.

White historical and dominant narratives dictate that there are singular binaries in which to know the self. White people born in Australia often describe themselves as «just Aussie», assuming that whiteness is the norm. The most racist amongst them expect you to quantify your Aboriginality in terms of percentage: «half white, half Aboriginal». This is a form of genocidal erasure that denies the wholeness of Aboriginality. There is no half belonging to your family or culture. You either are Aboriginal or you are not. The knowing of the self, the being yourself, comes from others: in my case my matriarchs; my family and community belonging and participation; my naming as Koorie, Aboriginal, First Nations; my mob, my clan, my language. My Country.

There are correlations between these ways of being and being named. My mother wasn’t given a choice in naming me, though she was able to give me my middle name, by compromise with my Calabrese father. He informed my mother that I – like four of my other female first cousins – would carry my patriarchal grandmother’s name, Paola. Many white people found this funny, and some touching; my name and its pronunciation has caused discern my entire life. Not many of my Aboriginal family could pronounce it, so they called me, as my mother did, Paula – the English spoken version. But the name is still written as Paola – which resulted in people calling me a variety of mispronunciations. I considered changing it, but I decided to honour it because I would never have disrespected my Aboriginal grandmother in this way. I tolerated people mispronouncing my name until I was about 38, when I decided to insist that people at least attempt to pronounce it, to resist the flattening of anglicizing names.

My Italian accent is terrible, and my Italian is non-existent, failed attempts to teach me on school holidays (the only time I saw my father or his family each year) was too difficult. I picked up basics, like «Paola, veni ca!» (Come); «Sette» (Sit); «Volu mangiari» (I want to eat); acqua, carne, pollo, and other names for food. I would blush with shame when old relatives would greet me, pinching and smothering both my cheeks with double kisses. «Paola! Bella, come stai? How’s your mother? Your grandmother? Your brother?».

I would falter and attempt, «bene, grazie!» (good, thanks!).

After I was greeted, the conversation would float away from me into Calabrese dialect, with aunties and uncles staring at me, assessing my second-hand clothes, my lack of gold jewellery, knowing I had not been confirmed in the Catholic Church: wondering how I could function outside of their lived reality. I knew that my world, my little black, Koorie, country town life was so radically different to theirs that they could never know because they never saw it. The road between us only went one way, from Echuca to Tottenham, from Echuca to Footscray. Yorta Yorta Country to Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung Country. Me, to them. Then me home to Mum, family, mob and community and Country.

Without language and the codes embedded within, I was lost. We were largely without Wemba Wemba, our matriarchal language, after it was banned during colonisation and English was enforced on our Peoples (relearning our Wemba Wemba language has been undertaken by a few family members now). Being proficient in only English was also a barrier to deep communication with my migrant grandparents. But I over relied on my English-speaking cousins to carry me through these times. Some tried to teach me, some confronted me as to why I wouldn’t choose to live with my father and his family instead of my black mothers. Others scolded this cousin for upsetting me.

Like the girls in Hey Sista that Matteo Dutto writes about in this Forum, Aboriginal sisters of mine invited others into our circles, and we still do, if with trepidation, giving isolated and rejected people space and belonging. I felt loved and feel loved by my father’s family, but still feel disconnected, like a visitor that still doesn’t quite fit. There is a country town colloquialism that you are only a local after you live somewhere for at least fifty years. Perhaps after fifty years I will feel like a local in my father’s family?

Fifty years is a short time line in this country, but a long time for an immigrant, asylum seeker or refugee to start to belong. The same towns in which they live saw Aboriginal people relegated to fringe dwelling in border towns, outside of white dominant structures like pubs, schools and shops. Relegated once off the missions and reserves onto the fringes of towns that manage our presence, erase our histories and erect monuments to genocidal governors, «pioneers» and convicts. In towns and cities where Aboriginal people die in jail cells, historically and continually, Aboriginal Deaths in Custody have continued since the 1991 Royal Inquiry into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, with four hundred and seven Indigenous people dying in custody since then (Wahlquist, Evershed and Allam, 2018).

A significant shift towards avowing the un-ceded sovereignty of Indigenous peoples over our colonised lands must become a crucial part of any attempt to establish and consolidate new dialogues and alliances between diasporic Italian communities and First Nations people. In creating new spaces of dialogue, reciprocity and collaboration, diasporic Italian communities must support Aboriginal communities in the daily healing, repair and responses to structural violence and racism, including the ongoing deaths in custody.

The young activist and scholar, Latoya Rule, in writing of her brother Wayne Fella Morrison’s death in Yatala prison in South Australia, noted that her mother was sent an invoice for one thousand dollars for the six days her brother spent on remand (Rule 2018, p. 14). The insult an additional injury to the violence of the settler state.

How valued is capitalism, settlement and empire building by Italian migrants? Can migrants transcend and unpack and ultimately dismantle the systems of privilege afforded to them by developing insights about the impact of their «new country» on Aboriginal lives and communities? And can they understand that beneath this lies Country belonging to Aboriginal Peoples who have been disadvantaged to their benefit? Solidarity and decolonial work require, well, work. Something not foreign to Italian migrants. Unpacking and dismantling where their racist attitudes towards Indigenous Australians emanates from is the beginning of unknowing.

It’s hard to remember people if you have already participated in their erasure to accommodate your own passage to place, home and the future of your descendants. When Italian migrants’ children and grand-children ask how and why they came to be in Australia, do they ask at whose cost? In Australia, the United States, or Canada, whose Native American or First Nations homelands are they on?

As an Aboriginal woman, I not only inherit culture, language, practice and knowledge, but trans generational trauma caused by the invasion, genocide and ongoing colonisation of our Peoples and Country. This trauma is both historical and contemporary. It’s the cost that genocide and white progress has had on the body of Aboriginal women in this country (Baker, 2017).

I am drawing on our collective situating of ongoing traumas and experiences and on the significant and rigorous work of global Indigenous, black and Aboriginal academics, writers, artists and community workers who name trauma as an ongoing legacy. This legacy is contextualised and conceptualised by Aboriginal peoples and is named within the de-colonial project.

Situating these collective traumas acts as a framework in my work and in my doctorate, as a sovereign practice. It is not just lived experience, but it is about placing it in the context of what others have done before me and do around me. My discourse references the work of Linda Tuhawi-Smith’s Decolonising Methodologies (2012), Aileen Moreton-Robinson’s Towards an Aboriginal Feminist Standpoint Theory (2013) and Tracey Bunda’s writing on the Sovereign Aboriginal Warrior Woman (2007) as both global, Indigenous, de-colonial methodologies and theories.

I live with trans generational trauma, and attempt to recover from both the past and present concurrently. I look to the future for healing and for my children’s. I am aware of the specific set of Indigenous ethics, obligations, and responsibilities that I am accountable to and that enable me to talk from a de-colonial and Aboriginal feminist standpoint in this space.

New ways of listening for diasporic communities require learning about respect, consideration and reciprocity as Indigenous practice (Smith, 2012) and learning about Indigenous theories and standpoints. This requires reconsidering the places that the diaspora have acquired to recreate place. It includes the acknowledgement that Country itself «holds» rights, memory and experiences of trauma, such as massacres, children being stolen, women being kidnapped and of sexual violence. It requires lifting back layers of «ownership» and looking at sites of cultural significance and cultural renewal that assist healing from historical and continuing traumas. I recognise that Indigenous research is an act of ceremony and honouring of Indigenous sovereignty and place making (Wilson, 2008).

Without awareness, migrants to Australia adopt racism towards Aboriginal people as a passage of assimilation. Hatred of Aboriginal peoples is a rite of passage that bonds all «others» within White Australia. During the public Forum, the presentation of rape statistics of Aboriginal women by Italian men in the Northern Territory by Pallotta-Chiarolli did not shock me. But it put my personal experiences, and that of my mother, into perspective. Ours was not just personal or intimate violence enacted by my father, but by many Italian men who saw Aboriginal women as disposable and usable; a violence that was widespread across the nation.

My research situates the work of Aboriginal women artists as visual authors of their lives and the lives of their families, community experiences and stories. My project relates to artists like Tracey Moffatt (1989), Destiny Deacon (1995), Karla Dickens (2016) and Lisa Bellear’s (1990-2007), for their clear disruptions of patriarchal colonial dominance.

Figure 2. Tidda Murrup,(ghost sister)

Source: Paola Balla with original image by Rosie Kalina, 2011

A patriarchal non-Indigenous view of art and art making as either traditional or contemporary art remains a dominant and highly problematic paradigm. It falls into a debate around notions of Aboriginal authenticity that distracts from the real work of de-colonising (Smith, 2012). The authenticity argument, as articulated by Smith (2012), is a global issue that ties Aboriginality to a male, nameless body. As stated by Moreton-Robinson (2016) the colonial project is a male story that erases Aboriginal women’s presence, contributions and humanity. As sovereign matriarchal women we speak back and blak (Deacon, 1990) to the violence, trauma and silencing of structural trauma encountered in daily life, the academy and public spaces.

Decolonising the history of the Italian diaspora will require a deep consideration of complicity in racism, capitalism and various forms of violence. This cannot be done without listening to Aboriginal women artists and activists’ practices of resistance, such as naming traumas and critiquing structural oppression. By situating the art and activism of Aboriginal women a space is created in which to consider endurance and resistance: a space for culture, beauty, truth and love.

Perhaps the numerous bodies of art and literature created by Aboriginal women can be places for the Italian community diaspora to begin the process of de-colonial reflection and critical self-analysis: to reflect on their place and role in unknowing so-called Australia.

Notes

1 The term ‘blak’ was coined by artist Destiny Deacon in 1990 and names the lived experience and identity of urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Destiny Deacon is a renowned photographic artist, born 1957 and her language groups are Kuku, East Cape Region, Erub of the Torres Strait region.

2 «Wog», in the uk, is a derogatory and racially offensive slang word referring to a non-white, or darker-skinned white person, including people from the Middle East, North Africa, the Indian subcontinent, other parts of Asia such as the East Indies, or the Mediterranean area, including Southern Europeans. A similar term, wop, has historically been used to refer to Italians.

In Australia, the term «wog» refers to residents of Southern European, Mediterranean or Middle Eastern ethnicity or appearance.

Bibliography

Baker, A. G., «Artist Talk», Next Matriarch exhibition, Ace Open, Taranthi National Contemporary Indigenous Art Festival, 2017.

Bunda, T., «The Sovereign Aboriginal Woman», in Moreton-Robinson, A. (ed.), Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous sovereignty matters, Crows Nest, nsw, Allen & Unwin, 2007, pp. 75-85.

–, «Seeing the Sovereign Aboriginal Warrior Woman», The Lifted Brow, 40, 2018, p. 5.

Ginibi, R., Haunted by the past, St Leonards, nsw, Allen & Unwin, 1999.

Langford, R., Real deadly, Sydney, nsw, Angus & Robertson, 1994.

Moreton-Robinson, A., Talking Up to the White Woman: Aboriginal Women and Feminism, University of Queensland Press, 2000.

–, «Towards An Australian Indigenous Women’s Standpoint Theory A Methodological Tool», Australian Feminist Studies, 28, 78, 2013, pp. 331-47.

Rule, L., «Sovereign Debt», Blak Brow, 40, 2018, pp. 14-15.

Smith, L. T., Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Dunedin, Otago University Press, 2012.

Tucker, M., If Everyone Cared, Sydney, Ure Smith, 1977.

Wahlquist, C., Evershed, N. and Allam, L., We examined every indigenous death in custody since 2008, this is why, «The Guardian», 28 August 2018, in https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/aug/28/we-examined-every-indigenous-death-in-custody-since-2008-this-is-why.